As we honor leaders in Black history this month, the battles they lead for civil rights may seem like relics of a past era. But there is more progress to be made to achieve systemic equality for Black people, particularly in the realm of voting rights, economic justice, housing, and education; as well as ending police brutality and eradicating racism and discrimination in the criminal legal system. Those battles continue under the leadership of Black activists, lawmakers, athletes, actors, and others — many working side by side with the ACLU — who are pursuing true equality to this day. This year, we’re recognizing both.

Thurgood Marshall

Supreme Court Justice, ACLU board member from 1938-1946

Yoichi Okamoto

As one of the foremost leaders of the civil rights movement, Thurgood Marshall was the architect of a brilliant legal strategy to end segregation and fight racial injustice nationwide. He’s best known for Brown v. Board of Education, a landmark 1954 Supreme Court case that dismantled the “separate but equal” precedent, initiating integration in schools and other parts of society. Before becoming the first Black Supreme Court Justice in 1967, he worked with the NAACP, founded the Legal Defense Fund, and served on the ACLU board for eight years.

“Where you see wrong or inequality or injustice, speak out, because this is your country. This is your democracy. Make it. Protect it. Pass it on.” — Thurgood Marshall, commencement address at the University of Virginia in 1978

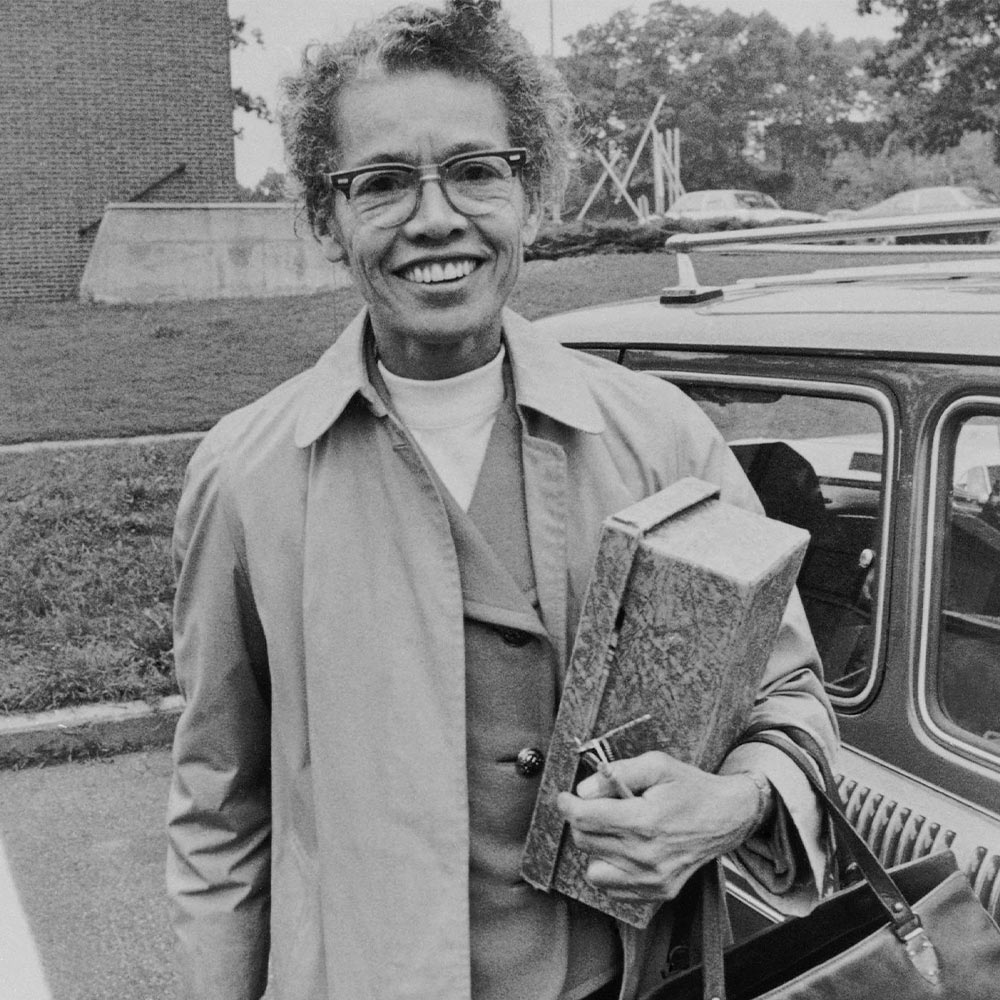

Pauli Murray

Lawyer and legal theorist, ACLU board member

Associated Press

One of the greatest legal minds of the 20th century, Pauli Murray was among the first to theorize that the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under law could be used to challenge laws that discriminated based not only on race, but also on sex. This work formed the basis for arguments in Brown and laid the framework for Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s mission when she founded the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project in 1972.

Murray also co-founded the National Organization for Women in 1966, but eventually left the organization in protest of its exclusionary racial politics that Murray believed did not address the barriers faced by Black women.

“Since, as a human being, I cannot allow myself to be fragmented into Negro at one time, woman at another, or worker at another, I must find a unifying principle in all of these movements to which I can adhere … This, it seems to me, is not only good politics, but also may be the price of survival.” — Pauli Murray in a letter to the National Organization for Women

In addition to Murray’s foundational work in women’s and civil rights, Murray also served the ACLU on its national board of directors and as part of an advisory committee guiding its women’s rights work. This past fall, we launched the Pauli Murray Fellowship in Murray’s honor — a program that will foster the next generation of leaders.

Winfred Lynn

ACLU client

Duke University / Broadsides and Ephemera Collection

When Black landscape gardener Winfred Lynn received his draft notice in 1942, he responded by defiantly stating that he was “ready to serve in any unit of the armed forces of my country which is not segregated by race.” The ACLU took up his case challenging the racially segregated draft in World War II. While the lawsuit itself ultimately failed, the controversy surrounding it highlighted the hypocrisy of segregating the armed forces of a country espousing ideals of equality during its fight against the Nazis. This case was a contributing factor in President Truman’s July 26, 1948 executive order ending racial segregation in the military.

W.E.B. Dubois

Founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

Associated Press

On the launch of his groundbreaking 1903 treatise “The Souls of Black Folk,” W.E.B. Du Bois remarked that “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.” In describing the Black American experience as a form of “double consciousness,” he created a theoretical framework still widely used in sociology today. Du Bois went on to found the NAACP in 1909, and became one of the most influential figures in Black history.

“One ever feels his twoness — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, who dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” — W.E.B Dubois

Laverne Cox

Actor and Trans Rights Activist

Andy Kropa /Invision/AP

As the first openly trans Emmy nominee, Laverne Cox has used her rising fame to advocate for trans rights, awareness, and visibility, particularly for Black trans women, who face criminalization and disproportionate violence and harassment. A frequent partner, she’s fought side-by-side with the ACLU against anti-trans legislation and at the Supreme Court, where she was instrumental in raising awareness for the Aimee Stephens case, in which the court ruled that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964’s protections against sex discrimination in the workplace also apply to LGBTQ people — a major victory for the rights of trans people across the country.

“I think part of this is a backlash against the unprecedented visibility we have in the media now. Trans people are coming forward and saying, ‘This is who I am. I have a right to exist.’ We’ve always existed, and now we’re coming out of the shadows. And as we come out of the shadows, people want to force us back into the dark and to back pages. And we are saying, ‘No, we deserve a right to live in the light.’ And that’s all we want.” — Laverne Cox in Democracy Now!

When Colin Kaepernick knelt during the national anthem before a NFL game in 2016, the “take the knee” movement was born as a widespread, powerful form of protest against police brutality and racial inequality, raising awareness on a national stage. While this act cost Kaepernick his NFL career, it made an indelible impact on the national conversation about race and policing, and the ways we protest.

“There are bodies in the street and cops are getting paid leave and getting away with murder … I am not looking for approval. I have to stand up for people that are oppressed. If they take football away, my endorsements from me — I know that what I stood up for is right.”— Colin Kaepernick

More recently, Kaepernick has worked on a docuseries on police brutality, “Killing County;” wrote a children’s book, “I Color Myself Different;” and appeared in a Netflix series about his life, “Colin in Black and White.”

Eleanor Holmes Norton

Congresswoman and former free speech attorney at ACLU

NDZ/STAR MAX/IPx

As a young activist fighting against racial segregation, Eleanor Holmes Norton took her passion for the First Amendment to the ACLU, where she worked as an attorney fresh out of law school, and later, to Congress, where she has represented the District of Columbia since 1991. Her work as a Congresswoman centers on full voting representation and economic justice for the people of D.C., and includes fighting for D.C. statehood, lowering college tuition, and housing reforms. In January, she announced the Senate introduction of her D.C. statehood bill, bringing it one step closer to passage.

“Growing up in the District of Columbia was ample preparation for the civil rights movement, not only because of racial segregation in the nation’s capital, but also considering that D.C. was directly controlled by the federal government until the 1973 Home Rule Act and had no mayor or city council, and no member of Congress. Deprived of the basics of democracy, compelled to abide by racial segregation, and denied representation in Congress, my hometown prepared me to look to the First Amendment for change.” — Eleanor Holmes Norton

Yashica Robinson

ACLU client, OB-GYN

Dr. Yashica Robinson has been on the front lines of the fight for abortion rights as an obstetrician-gynecologist serving her community in Alabama. With representation from the ACLU, she fought for years to keep Alabama’s near-total abortion ban from taking effect and to keep abortion available in the state. Even though that ban finally took effect last year after the fall of Roe, she continues working tirelessly for reproductive freedom.

“Black women in Alabama are nearly five times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women. We know that racial disparities in health care are exacerbated by policies that make accessing health care more challenging. Without access to abortion, maternal mortality rates will rise even more — in Alabama, and across the country.” — Yashica Robinson

LaLa Zannell

Trans Justice Campaign Manager, ACLU

Associated Press

As a Black trans woman and leader in the trans rights movement, Lala Zannell has fought discrimination, criminalization, and violence against trans people with the ACLU and as a community organizer. Protecting Black trans lives is a priority of her work, which includes helping to end unconstitutional searches by the NYPD, advocating for the decriminalization of sex work, and testifying at the first Congressional forum on violence against transgender people, among other initiatives. In 2017, she made history as the first trans woman to speak at the White House for Women’s History Month.

“I was not all the way 100 percent, a publicly out visible trans woman … It was not until after Islan Nettles died — who was a Black trans woman out of Harlem who was in school, she just got her apartment, was on her way to FIT university for fashion, was trying to go home. And a guy cat-called her. She told her truth and he beat her to her death. … to just see so many Black trans women, Black queer people mourning the life and death of a Black trans woman was just so powerful for me. So in that moment, I just said I don’t care anymore.” — LaLa Zannell