May 13, 2019

Updated: July 31, 2019

Introduction

Racial disparities pervade criminal justice systems across the country; Washington, D.C. is no exception. The District of Columbia’s Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) recently provided extensive “arrest”[1] data for the years 2013 to 2017 in response to a Freedom of Information Act request filed by Open the Government and ACLU-DC. An analysis of that data revealed a pattern of disproportionate arrests of Black people that persists across geographic areas and offense types. It also showed that MPD arrests thousands of people every year for relatively minor offenses. This report analyzes these trends and proposes steps for addressing them.

Clear Disparities -- No Matter How You Cut the Data

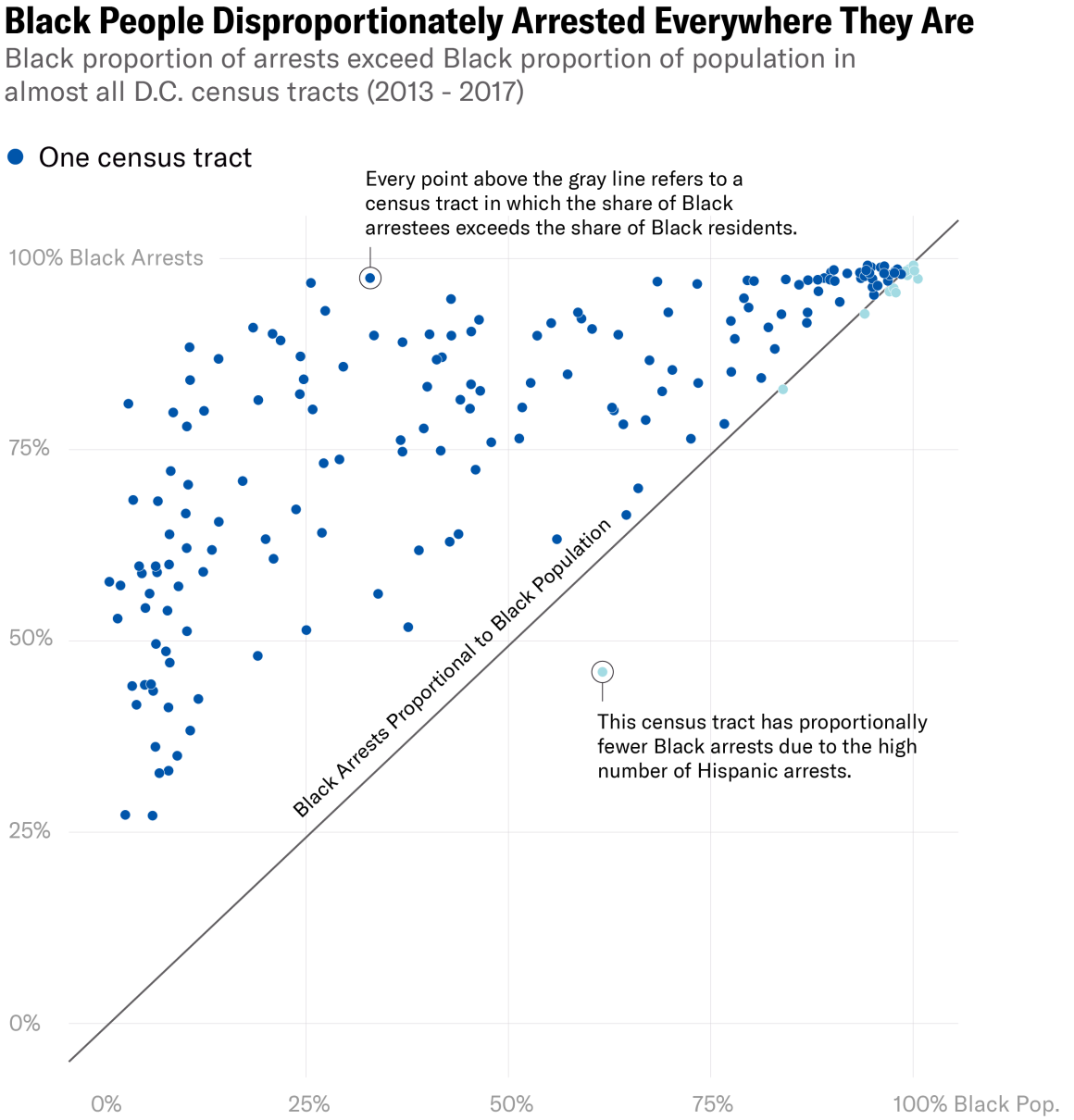

From 2013 to 2017, Black individuals composed 47% of D.C.’s population but 86% of its arrestees. During this time, Black people were arrested at 10 times the rate of white people.

This disparity cannot be explained merely by a large concentration of MPD officers in predominantly Black neighborhoods. Rather, as the graph below shows, Black people are disproportionately arrested in over 90% of the District’s census tracts, including the whitest parts of the city.

CHART 1

Traffic Arrest Patterns Raise Particularly Serious Questions about Racial Bias

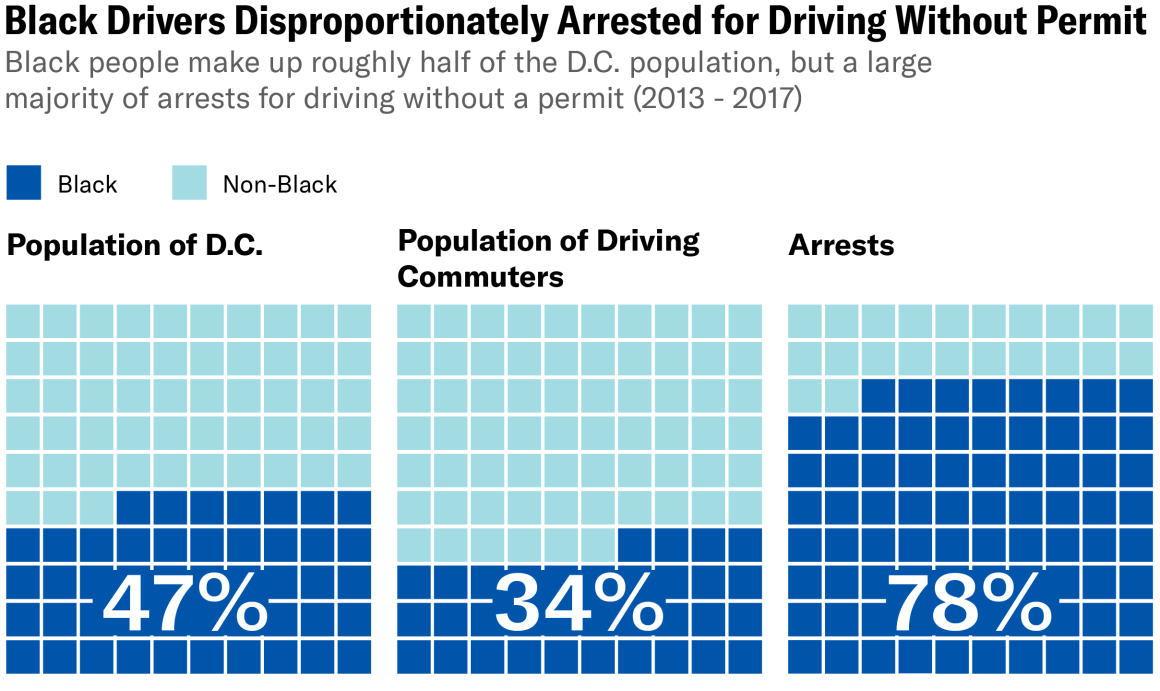

Seventy-eight percent of all people arrested for driving without a permit were Black. That statistic is notable because in many cases, officers have no way of knowing whether a driver possesses a valid permit at the time they order the driver to pull over.

As a result, the significant disparity in arrests for this offense may indicate a racial disparity in traffic stops—which, in turn, could arise from discriminatory decisions by officers.

CHART 2

Unfortunately, we can’t assess whether such a relationship exists because MPD has dragged its feet tracking crucial data about police stops and making the information it does collect meaningfully accessible.

Large Numbers of Arrests for Nonviolent and Minor Offenses

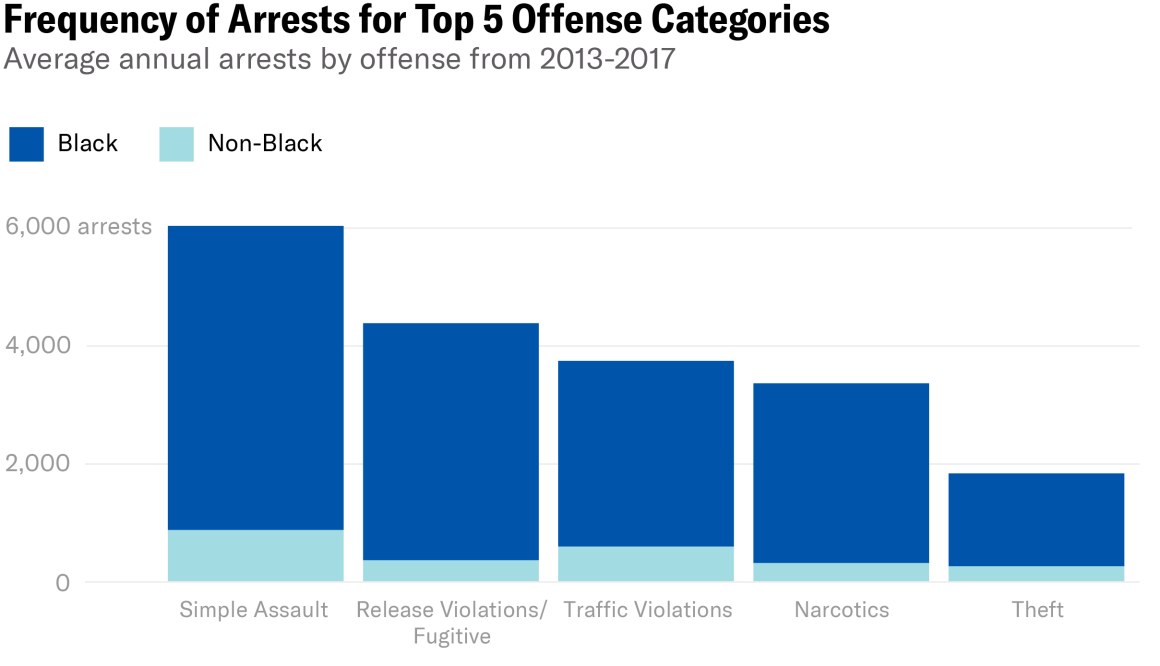

Arrests for nonviolent offenses constituted a significant share of the overall arrest total for 2013–17. Indeed, of the five offense categories that generated the most arrests, four—release violations, traffic violations, narcotics, and theft—primarily cover nonviolent forms of misconduct. The chart below, which shows the average yearly arrests for the most common offense categories, illustrates this point.

CHART 3

Some nonviolent offenses are serious; however, thousands of MPD’s arrests were for relatively minor ones. The table below describes arrest patterns for a few of those offenses.

Table 1

Offense | Number of People Arrested | Percentage of Black Arrestees |

Driving without a Permit | 10,305 | 78% |

Possession of an Open Container of Alcohol[2] | 4,725 | 80% |

Public Marijuana Consumption[3] | 532 | 80% |

Gambling | 667 | 99% |

Noise Complaints | 412 | 76% |

To interpret this data, it is important to note that not all of the arrests for the offenses listed above involved instances where officers took suspects to a police station. For some offenses—including possession of an open container of alcohol, public marijuana consumption, and noise complaints—officers have discretion to respond by issuing a citation rather than taking a suspect into custody. With respect to those offenses, MPD defines the term “arrest” to include both responses, meaning that, for at least the three offenses mentioned, the numbers reported in the table include non-custodial as well as custodial arrests. At this time, MPD has not made public the number of “arrests” that that are non-custodial in nature.

Granting officers discretion to issue citations in lieu of custodial arrests is a step in the right direction. However, for many offenses, officers lack such discretion. For example, MPD requires officers take people into custody when they are suspected of driving without a permit, even though officers could respond by issuing a citation and either towing the car or asking the suspect to call a friend to drive it away. More generally, the fact that officers can issue citations for a subset of offenses does not disturb the main finding presented in Chart 3: offense categories composed primarily of non-violent offenses still make up four of the five categories that generated the most arrests from 2013–2017, even when excluding offenses for which officers can issue PD Form 61 D citations and Notice of Infraction citations.[4] Thus, although MPD allows officers to issue citations in some cases, its current rules have not prevented officers from taking a large number of people into custody for engaging in non-violent or relatively minor forms of misconduct.

If the District truly wanted to address this issue, it could take more concerted action. For example, Mayor Muriel Bowser could work with the D.C. Council to decriminalize relatively low-level misconduct. She also could require that officers issue citations for low-level offenses rather than granting them discretion to do so—a change that MPD made with respect to public marijuana consumption in 2018.

The need for such reforms is particularly significant given that tolerating custodial arrests—or for that matter, citations—for relatively low-level offenses likely disproportionately affects Black residents. That’s particularly true of the crimes highlighted above—many of which indirectly constitute poverty crimes. Consider open container laws. Because people in poverty are less likely to own property than wealthier individuals, they have fewer private places to congregate with friends. That makes members of low-income communities more likely to gather in public—and commit open container violations if they drink alcohol while doing so.

Given the high correlation between race and poverty in the District, arresting people for crimes that are disproportionately committed by people who are poor will result in more arrests of Black residents, however the term “arrest” is defined.

One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

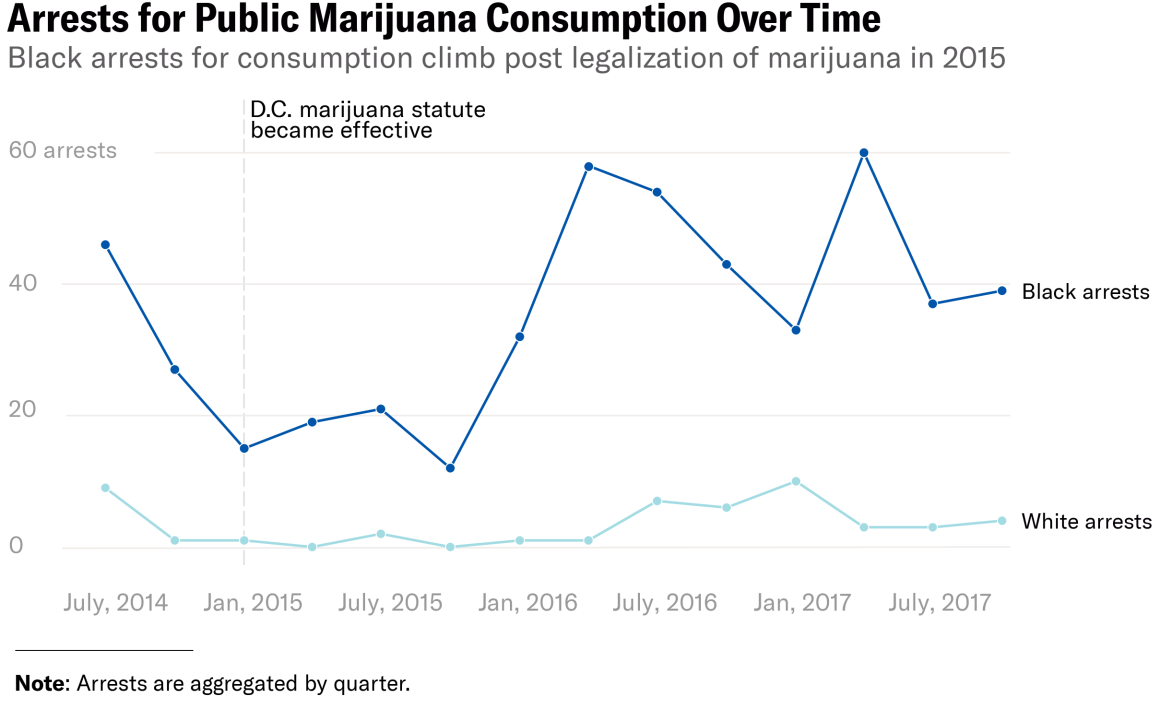

Passed in 2014, Initiative 71 made it legal for people to possess, use, grow, and share small quantities of marijuana. The law does not authorize individuals to consume marijuana in public or sell the drug to other people. As a result, public consumption and distribution remains illegal.

The marijuana statute became effective in February 2015 and, that year, the overall number of arrests for marijuana-related offenses plummeted, from 1,747 arrests in 2014 to just 216 arrests in 2015. The drop was largely driven by the reduction in arrests for marijuana possession.

CHART 4

However, while arrests for marijuana possession remained low, the number of arrests for public consumption of marijuana has been steadily increasing, particularly for Black people. After marijuana legalization, consumption arrests briefly declined before starting to rise, increasing from 79 arrests in 2015 to 217 in 2017.[5] Arrests for that offense are racially skewed: even though white and Black D.C. residents use marijuana at similar rates[6], Black individuals comprised 80% of the individuals arrested for marijuana consumption from 2015–2017.

This disparity could stem from officers’ racial bias. Alternatively, the disparity could be the result of another statute that makes it illegal to do in public what is legal to do in private—thereby penalizing those who have less access to private property. These explanations could also work in tandem. No matter the cause, the consequence of the current marijuana regime is that Black people are ensnared in the criminal justice system at disproportionate rates for what the D.C. government agrees is a minor offense.

How Can We Move Forward from Here?

D.C. has one of the highest rates of officers per capita in the country; its annual budget is $500 million. Mayor Bowser has proposed increasing that budget by an additional $3 million so the Department can hire more officers. That’s not the right approach: the racial disparities documented here should prompt further analysis—if not outright reform—rather than an increase in the number of officers.

Rather than give MPD money to hire more officers, the mayor should:

- Encourage the Council to repeal criminal statutes when they disproportionately target people in poverty. The Mayor and Council should consider introducing legislation that would repeal statutes that often penalize people for being poor. At a minimum, Mayor Bowser should order MPD to respond to these types of low-level offenses with citations rather than custodial arrests.

- Collaborate with the Council to expand the power of the D.C. Office of Police Complaints (OPC). District law grants OPC the power to review incidents of police misconduct but significantly limits the circumstances in which OPC can exercise that authority. For example, OPC investigators can only issue reports based on the specific conduct raised in the complaint that the Office receives. That means if a complaint asserts that an officer was rude, but neglects to mention that the officer also used excessive force, OPC investigators could not open an investigation into the excessive force, even if they have incontrovertible evidence that it occurred. Restrictions of this sort hinder true accountability. D.C. Council Bill 23-0320 would eliminate these barriers by allowing the executive director of OPC to “[i]nitiate his or her own complaint against” officers upon noticing misconduct not alleged by the complainant. Mayor Bowser should support this legislation.

- Open an independent investigation into MPD’s Narcotics Special Investigations Division (NSID). During a recent officer disciplinary hearing, J.J. Brennan, a retired MPD sergeant who had worked in NSID and was still serving as a civilian supervisor, revealed that, when he was a sergeant, he routinely instructed officers to conduct invasive searches of suspects’ groin areas. Consistent with this testimony, several community members have complained to ACLU-DC about NSID officers committing searches of the sort Brennan described. In the face of credible allegations of grave misconduct, Mayor Bowser should demand answers by establishing an independent body outside MPD to investigate how NSID conducts searches. UPDATED July 31, 2019 – The D.C. Council funded this investigation in its latest budget. Now, it is MPD’s responsibility to fully comply with that mandate.

District residents deserve a police force that serves them without bias. This report raises important questions about whether MPD is achieving that ideal. Mayor Bowser should demand that MPD release the data necessary to analyze the trends highlighted here and work with the Council to implement the reforms necessary to reverse them.

[1] UPDATED July 31, 2019: After this report was published, a researcher with the Vera Institute of Justice informed us that, with respect to a relatively small subset of offenses, MPD defines the term “arrest” to include instances where officers issue citations as well as instances where officers take suspects into custody. At this time, MPD has not made public the share of “arrests” that fit each category. No matter the definition, the data shows that MPD officers disproportionately arrest Black people in D.C. To the extent that the definition of “arrests” affects other aspects of this report’s findings, we have revised accordingly.

[2] As defined here, this offense excludes people arrested for public drunkenness or possessing an open container of alcohol in a vehicle.

[3] Data from 2015 to 2017, after legalization of personal possession of small amounts of marijuana.

[4] MPD officers also can issue a third type of citation known as a Notice of Violation. To our knowledge, the Department has not publicly released a list of offenses for which officers can issue that citation. As a result, we cannot assess the impact of Notice of Violation citations on the main findings presented in Chart 3.

[5] In 2018, MPD prohibited its officers from making custodial arrests for public marijuana consumption; the Department continues to enforce the statute through citations.

[6] See, e.g., National Survey on Drug Use and Health: 2-Year RDAS (2016 to 2017), Substance Abuse & Mental Health Data Archive, https://rdas.samhsa.gov/#/survey/NSDUH-2016-2017-RD02YR/crosstab/?column=MRJYR&control=STATE&filter=STATE%3D11&results_received=true&row=RACE4&weight=DASWT_1 (click “Run Crosstab” to view results) (last accessed May 10, 2019).

Date

Monday, May 13, 2019 - 10:30amFeatured image